As is often the case, the first-due rig cannot fully trust the information it gets through dispatch until the crew arrives on scene.

That’s exactly what happened to the Springville Fire and Rescue C-shift in mid-October.

Springville is located in central Utah in the Provo-Orem metro area with a population just over 35,000. The combination department is staffed 24/7 with 5-6 personnel daily. The department has 18 full-time, 12 part-time and 36 volunteer firefighters. It is an all-risk fire and EMS department. We cover a call volume of approximately 2,200 calls annually out of one station. All members are certified at least to the hazmat operations level.

Also Read: Drill for Community Air Monitoring

On the evening of Oct. 11, Station 41 C-shift, was dispatched to a reported residential structure fire. Reporting party was a passerby and unable to stop. The caller stated flames were visible shooting directly up into the air and was directly impinging an outside deck. Springville Fire and Rescue Engine 41 and Ambulance 41 arrived within 5 minutes.

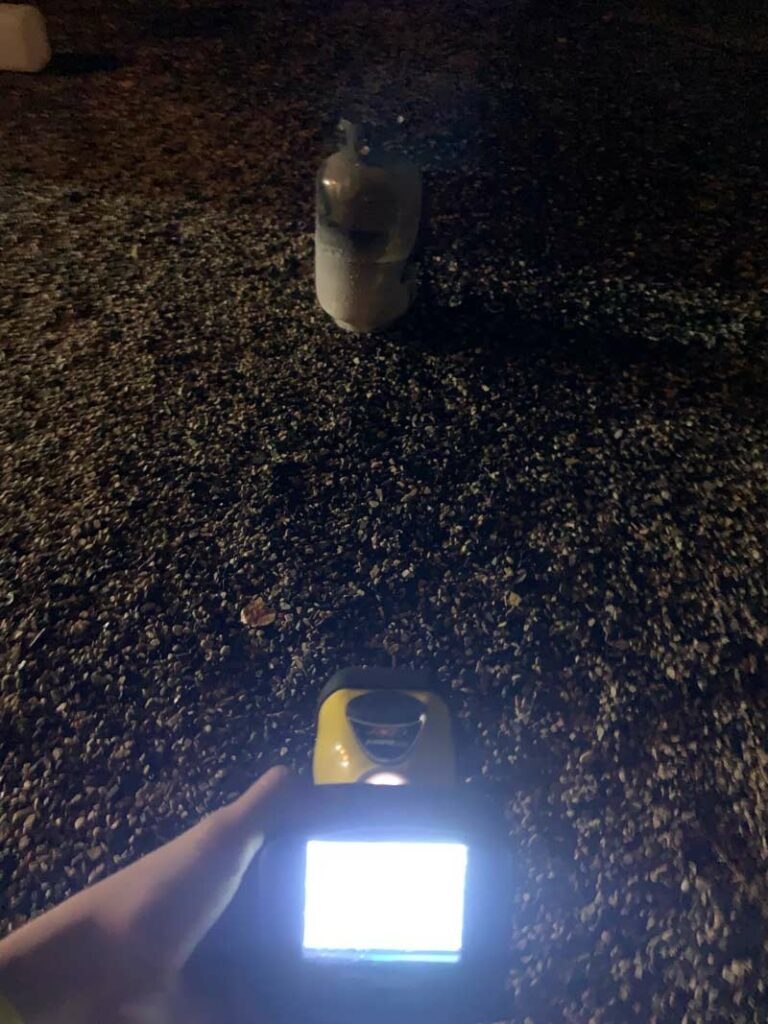

There was initially difficulty locating due to caller not giving an exact address. Once located crews found smoldering wooden appliances accompanied with a small, 20-pound (5-gallon) propane tank actively leaking. The assignment was downgraded from a structure fire to a gas leak.

Also Read: NIOSH: Why Firefighters Must Understand Multi-Gas Monitor Readings

Engine 41 was staffed with four personnel, two of which were hazardous materials technicians. It was determined the crew would remain on scene and allow the tank to release its contents while monitoring conditions.

The homeowner stated the tank began venting while he was inside eating what had been cooked on the propane grill. He said he heard a loud whistling sound, accompanied by flames. He also said he was busy trying to extinguish the fire; 911 was not called until passersby reported it.

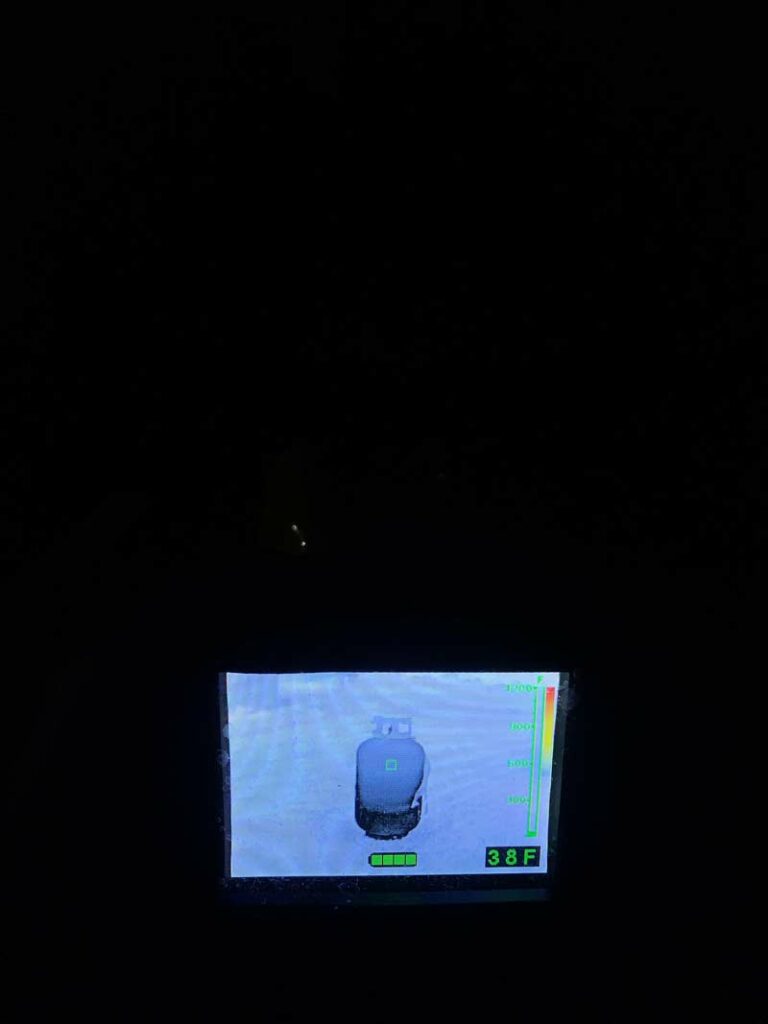

While allowing the tank to expel itself, crews on scene used the thermal imaging camera to assess how much of the contents had been expelled and what was remaining. The crew said this led to a great discussion on how this piece of equipment could be used on more incidents than they previously considered.

Experimenting with the TIC during the venting process the crew found the coldest temperature at the bottom of the tank to reach -6°F. The warmest point of the tank towards the top read 36°F. Ambient temperature was 57°F with calm winds.

Once the tank expelled to an acceptable level, crews released the scene to the homeowner and advised them to take the tank to a nearby propane facility.

Here are three lessons the department learned from this event.

ONE

Every incident has the potential for a hazardous materials release. This job is very dynamic and every scene is ever evolving. What initially began as a fire turned into a gas release.

TWO

Make full use of often overlooked equipment. The TIC proved to be a very useful tool, in that they knew at all times what the level of the tank was. They had a greater sense of awareness on the critical temperatures the tank may reach.

THREE

The details in the call notes don’t always include everything that is pertinent. Because the reporting party was a passerby and unable to stop, it was unknown this was a propane tank torching. This additional information could have prompted a different response and additional precautions enacted.